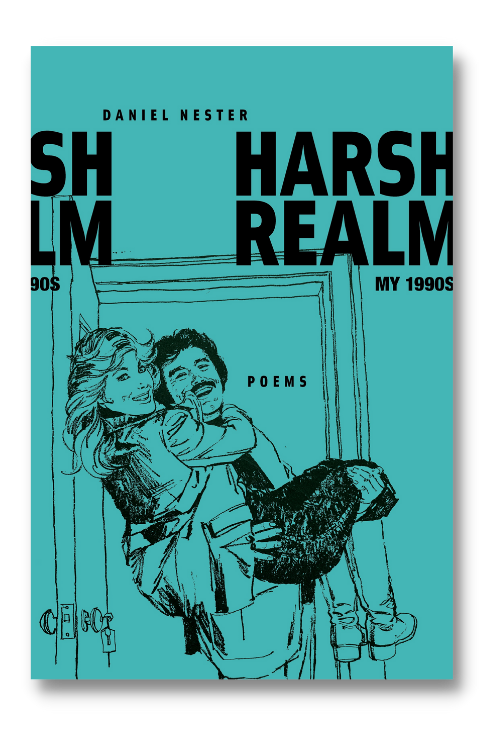

CS: Reading Harsh Realm, your first book of poetry in 15 years, I get a sense of the uncanny. In one poem you mention you lived at 16th and Spruce in Philly. I did too (probably a few years before you), but in deeper ways too, and I suspect my reading of the book is very different than readers who didn’t have somewhat overlapping interests and experiences of the time, like people born after 2001 or in other places? Did you imagine particular readers as you wrote this book?

DN: I am wondering—I have always wondered—who would want to read my writing, especially these days, at my age. I suspect there are shared sensibilities between us regarding how it fits into the Philly and NYC scenes—and I keep forgetting you got your degrees up here in Albany, where I’ve been since 2005. Of those three, it’s New York that was the most transformative and drenched in things that inform the present book. I get serious pre-1999 flashbacks of Philly in Albany: the smallness of the scenes, the territorial nature of staking claims to running little fiefdoms. And that’s outside of academia! It’s almost as if college towns beget parallel systems that both criticize and imitate the industries that dominate the area. Anyway. I don’t have loads of students interested in my work—I make a point not to talk about my own writing in class. I teach undergraduates who would much rather talk about their own writing, really.

CS: I admire your written “eye” skill for vivid sensory detail grounded in the lived experience of psyche and body of the speaker throughout Harsh Realm, and how you have a better memory, more visceral detail of the 90s than I have: To take just one early synesthetic example:

“…pogoing in the mud,

in Piscataway, hearing Michael Stipe

sing for the first time, I wore white jeans

and a Corona poncho. I cut off the jeans.

chucked the poncho, and wore a Murmur shirt” (pg. 17)

It is almost as if this sound demanded a style, a look, for instance. Virginia Konchan speaks of these as “remixed” poems. and I wonder if many of these poems in this book are rewrites (or say, samples) of poems, or notes, you wrote back then, but now seen from the point of view of a present speaker in a very different emotional state of being?

DN: That particular run of lines is expanded on in a chapter from a memoir I wrote called Shader. I do remember that concert pretty vividly, since at the time I was a new and rabid R.E.M. fan, listening to the first two full-length LPs, Murmur and Reckoning, nonstop. I suppose as a result of writing that, I did more online research I might have done if it was a poem. I confirmed that the R.E.M. gig, which was free and outdoors at Rutgers New Brunswick, was in fact in Piscataway, which just sounds great, and I also confirmed in the Old Farmer’s Almanac that it was rainy around that time.

I’ve always been self-conscious of the presentation of the self in everyday life. I’ve always suspected I didn’t fit in or obsessed over what others think or have thought about me. That R.E.M. gig was liberating in that I discovered people who didn’t care what others thought how they looked or acted, and felt I fit in. Now of course, that is another pose, and other persona one adopts. But it was a genuine liberation, as I recall it.

CS: R.E.M’s first two albums were crucial for me too. I like the way you counter the dominant myths of fashionable lifestyle music of the 1990s, in such early (space-clearing?) poems as “I can’t say punk was important…” (8) Not only does this poem, to me, perfectly capture the sense of belatedness our generation felt, but also that it was the glamourous “punk rock girl(s)” (as the Dead Milkmen put it) that drew many to become partisans of particular scenes; like for me there’s a sense that if these had been “goth girls,” you would have gotten more into goth?

DN: I like this idea of space-clearing, or maybe claiming. “I can’t say punk was important” is a bit of an answer-poem to some Diane Seuss poems I was reading in Frank: Sonnets, which as I write this has just won the Pulitzer. I love those poems, and there were a couple that seemed to embrace punk ethos in a way that just escaped me then, and from today’s vantage point feels very class-specific.

Goth, as a concept and in practice, eluded me at the time, and maybe still. At least by the late 80s, Goth and punk were pretty much one and the same in many social spaces and clubs I encountered, so the difference really wasn’t there to make. I understand what you’re getting at, that goth was a kind of “third way” to go, as much as maybe New Wave might be as well. Punk, or being “real punk,” was a genuine obsession in the late 80s and early 90s where I lived, in South Jersey and Philadelphia. I suppose it’s still something people obsess over. And “punk” is such an elastic term that it’s lost its meaning. But back then, to be punk cost money. It required access to money or you to be born into the kind of caste where money wasn’t a factor, so you could engage in that scene. If you were lucky enough to find yourself as a punk in a punk scene, then you were someone who had access to people who were wealthy or kids of the wealthy. It felt absurd to be inside some punk club where you just knew the kids were acting out a rebellions that didn’t register to me genuine as a working class kid. It seemed like rebellion karaoke. The worst part: I really loved the music, and couldn’t understand why you had to take some sort of aesthetic loyalty oath to be considered a true lover or punk.

CS: I hear you; I knew some of these rich kids too. In a way I felt they envied us poorer kids, it’s like when expensive boutique stores started selling pre-made ripped jeans. Anyway, reading this poem, alongside “Heavy Metal did not die in ’91” (14), a “we poem” that also, not without self-deprecating humor, becomes a working class anthem, given the sociological, class contrasts in these poems. In these poems, as well as the poetryland poems, I can’t help but identify with the frustrations of the speaker against what I call the OUGHTISTS. Against the backdrop of, say, that Thurston Moore documentary, “the year punk broke,” in which “broke” can be taken two ways, in these, as well, as “The Death of College Rock,” (17) I also find your interventions on behalf of the iconoclasts that these movements were ostensibly touted to free away from the trickle-down corporate demographic targetters to be appealing and refreshing. Is there anything you’d want to respond to here?

DN: I like that term, OUGHTIST.

CS: I borrowed it from Brett Evans.

DN: Interesting. The way I look at it, in my mind then and in the poems, is that all of this culture we’re talking about is mediated in some way, be it MTV or some Simon Frith book you pick up at a used bookstore or some group of middle-class kids in line for Cure tickets. There is no pure way to experience these things, and definitely not writing about these things. At the same time, there is no way moments listening to hair metal that can be just as genuine and heartfelt and sublime-approaching as any other cultural experiences. The issue I’ve always had, in music as well as poetry, is how the critical discourses that surround reception foregrounds middle and upper class reception, and not only discounts working class reception, but the art that working class people love. Remember Heavy Metal Parking Lot, the 1986 documentary of the Judas Priest/Dokken concert in Maryland? I remember watching it in the 90s and celebrating it as well as giggling at the metalhead fandom as well. I think it’s a powerful thing to be at once self-conscious and sublime-seeking when it comes to, say, listening to Dokken at the height of their powers. On top of that, there is this idea, in the “Nirvana killed hair metal” narrative, of some sort of good triumphing over evil. It’s maybe score-settling on my part in the form of a poem-as-barstool rant. But I see it in other pop music writing today. I am skeptical of the poptimism of the recent generations of music critics, but I guess that’s another topic.

CS: It’s interesting though! Of the pop-culture poems, “Nostalgia Ain’t What It Used to Be” reminds me both thematically and tonally to Burmese writer ko ko thett’s “my generation is best.” In contrast to these poems that read the self in terms of pop culture (and pop culture in self), “The Plan Shifted With a Ferocious Snap” portrays a speaker in the act of reckoning about his youthful recklessness. But this meditative “I used to” themed prose-poem is interrupted on several occasions by forces’ in the speaker’s present environment: the first is the noise pollution of a rant. When the meditation on the past resumes in the second stanza, the act of othering takes on more urgency, as it’s clear the older, more contemplative speaker, still must confront darker temptations to be reckless:

“One night, driving/out in the pines, I shut off the lights in my car, and took on the highway in the dark,/quiet, unmediated by light or sound or direction. I held a cold coffee in my hand,/waiting or wanting to hit some tree. I waited some more. Then the glow from my/phone lit up the interior.”

The “intrusion” of the phone turns out to be so much more. Was this a very difficult book to write?

DN: I can’t really say that the book as a whole was difficult to write, but I will say “The Plan Shifted With a Ferocious Snap” was a specifically difficult poem to write, primarily because it deals with reckoning with a death wish. Driving in the middle of South Jersey and turning your lights off and thinking or perhaps hoping to hit a tree or a wall, that’s not exactly what I would call healthy behavior. The memory has all kinds of moments around it—triggers, I guess I’d call them—most to do with going back home where all these memories lurk in the woods. And so as I think of the poem now, the cell phone call might have caused me to look away from the road and lead to an accident, but instead it snapped me out of it. If any poem in the collection should come with some sort of content or trigger warning, I think it’s that one.

CS: Did Harsh Realm germinate in you a long time? When did you first conceive of this book? Did you go back to scenes where these memories took place as research? You mention that you had written a memoir called Shader before the poems? Did you come to feel that there were things you wanted to say in the memoir that could only be said in poetry?

DN: Some of these poems have been knocking around a while, for years, while others came out in the past five years, after I wrote the Shader memoir. The poems cover the period after I write about in the memoir, for the most part. Why I decided to write about that period of my life in prose, and the next in poetry is something I still think about. One pet theory I have is there is something about writing about the 90s and the dawn of digital technologies that necessitates a fractured and even granular poetics. A single-paragraph prose poem seems to say on the page HERE IS A MOMENT. It says to the reader, that’s all there is. When of course there are connections to be made, perhaps with other single-paragraph prose poems in the book, but also with the white space on the page and whatever is happening in the reader’s head. Another pet theory I have is I don’t want to make those connections. There is a certain kind of false nihilism that comes out of the 90s, a product of prosperity and stupidity, borne out of a desire to seek out discomfort. That particular poem also has some echoes of Robert Lowell’s “Skunk Hour”—but for all the wrong or worst reasons. That idea of the speaker-as-voyeur moving around this othered space.

CS: At the Zoom Book release party I “attended,” you only read one of your “Poetryland” poems, as if you were purposely trying to spare the audience of mostly non-poets. While some of these poems, such as “From My Desk, c. 1997” and “This is Not a List Poem,” emphasize a critique of some prevalent aesthetics (I, for instance, certainly wrote my share of, in retrospect, cringe-worthy “list poems” during that time), in others, aesthetic & ethical arguments and ethics blur—for instance, in “Debate Outside The Four Faced Liar, 1999,” we see an oughtist bugging the speaker about the need for “a sense of play,” in a very unplayful, and annoying way, highlighting the (hypocritical) discrepant hubris in a hilarious (meta-playful) way.

DN: I do resist reading those “Poetryland” poems in mixed company. My assumption has always been that non-poet civilians just wouldn’t get those poems. But when you describe the nexus of ethical and personal and aesthetic concerns in those poems, it makes me think that maybe I could read more of them.

I published an essay years ago about leaving the New York City poetry scene called “Goodbye to All Them,” which laid out a couple aspects of how cruel and careerist poets in NYC can be. It kind of went viral, getting mentions in all these different mainstream places, and I started hearing from people all over about how it resonated with them. Like, someone from Kansas saying how it sounded like their scene, or some artist from Ireland and their experiences with, like, other landscape painters. The takeaway for me was that it’s not just poets who are subjected to a clannish ethical wasteland. I found that oddly reassuring?

In Harsh Realm, I think what I am writing about is slightly different. It’s more along the lines of retcon attempts or correcting the historical record. The one I did read that Zoom reading, “Two 90s Poetry Readings,” went over just fine, and that poem was about as inside baseball as you could get. Using initials instead of real names make the poems perhaps more universal or like 19th Century novels.

I will always lay claim to being a grump or snob about certain poems. It’s just impossible to love every poem and every poet’s work. Poetry is so vast in its approaches, I do think it always has fed on itself, in the best and worst ways.

In the middle of a reading I attended recently, a poet friend asked me, “Do you think it’s possible to hate poetry and love it at the same time?” And I totally got what they were asking. My answer to that is yes, yes, yes. I think it’s essential to hold onto the idea of anti-poetry and poetry in one’s head at the same time. And I bring this up because I think when I write about another poet badgering me about aesthetics—using a very 90s-type argument about elliptical poetics as a way of discounting personal experiences and “exposing” narrative as some bourgeois tendency, as I remember that debate now—I think about it with a kind of nostalgia. People really thought this was a life-or-death discussion, right outside a bridge-and-tunnel Irish bar in the Village! It seems quaint to think about it.

As a true product of the 90s, my main coping mechanism when faced with conflict is humor and ironic distance. The world of poets and forging alliances and networking and readings and editing small journals and promoting other people’s poems, back then, seemed like a full-contact interpersonal sport to me. It goes without saying that writing poems wasn’t enough.

CS: I find your portrayal of the toxic ethos and traumatizing dynamics of the mostly male-dominated scenes of that time to be compelling in ways that go beyond mere “score settling” and self-pity. Many of these character portrayals, and ethical critiques of other (unnamed) poetry scene types, such as “To The Heckler At My First Poetry Reading, 1994,” bring me back to that time with a lot of “uncanny feelings and unsettled bellyaches of energy” (8).

DN: That experience reading poems in a real venue as a 25-year-old and having this drunken poet heckle me the whole time was nothing short of traumatic. I didn’t want to write about it because I still feel embarrassed about it, all these years later. But I knew that if I was going to write about becoming a poet in the 90s, I would have to write about that awful night. I never looked this dude up, but I found out this person was not some chimera who appeared at the back of the Tin Angel folk club, but was in fact a member of the Philadelphia poetry scene. And maybe that’s why no one told him to stop? I’m still not sure. If anything, it made me happy to just leave Philly and start all over. If there is one thing I have learned about writing nonfiction, particularly memoir, it’s that if you’re going to write about someone who did something wrong to you, you need to at least examine your own motivations for writing about it. That poem about my heckler was something I could have written about for more than 30 years but didn’t. And that’s because I couldn’t. The guy still exists out there, and writes poems, and never thought to apologize. I’ve had drunken nights myself where I misbehaved, but I did that whole thing where I called the next morning and apologized. After writing the poem, I think I realized that this wasn’t one of those one-off things. I think this is just what happens in poetry and the one very valid coping mechanism is to write a poem about it.

CS: Yes, I think it’s very valid, and you handle it with grace and flare. When I read a sentence (from “More Poets”) like “whether this is a failure of the city, or merely/ of the poet, is an open question,” I remember how many of us younger poets (including myself), in poetry scenes at that time, in our attempts to dig ourselves out of the divisive pettiness we felt in elders, ended up falling into such cruel dynamics ourselves—in a way that just makes me want to escape from the whole “poetry scene” dynamic that tends to bring out the worst in people at least as much as today’s social media, with the temptation to speak before thinking, without any awareness of how we might come off to others.

DN: That’s completely true. I would like to think that, because now I am older and have other interests and am no longer so monomaniacally focused on poetry and poem-making, I am not as susceptible to the divisive pettiness you’re talking about. To be honest, I’m torn between trying to assert myself in some ways—writing poetry reviews, putting readings together, publishing journals—and think of that as a way to just be involved, as opposed to taking up space others could, and should, otherwise inhabit. It’s a relief, to be honest. I have been cruel in many of the same ways I write about, and some other ways I haven’t written about. I was really inspired by David Trinidad’s 2016 collection Notes on a Past Life—that poem “More Poets” is sort of an homage to one of the poems in that collection. The way Trinidad wrote in narrative and artful ways about a poet’s life felt both breezy and transgressive at the same time. Breezy because the poems are just eminently readable, filled with New York references from about a decade before my time, as well as all this yummy gossip that reads as sincere. It made me realize I could write narrative poems again in ways I’ve tried to avoid, for fear of being uncool or “mainstream” or some other nonsense. It also made me realize that I don’t mind writing for a coterie of other poets.

CS: I like breezy and transgressive; I feel that in your book too. Did you feel a sense of purgation digging through these “retcon” memories? By emphasizing the negative, were you responding to a feeling of 90s nostalgia that many are tempted to have these days?

DN: I feel a little purge-y when I read these poems. If I put in my self-promotional marketing hat on, I do think there is something in the air about the 90s now. Not only people who lived through the 90s but also people who are interested in it.

CS: Do you feel that, perhaps, these days, poetry scenes are more supportive of each other than they were then?

DN: I really don’t know. It’s kind of obvious, but scenes are as much more digital and virtual now as opposed to proximal and geographical. I do think that, in the last 30 years, poets who have professionalized themselves and have gotten really, really good at institutionalizing things that weren’t institutionalized before. We’re in a world where Submittable makes it possible to submit to hundreds of journals all over the country and the world, all without reading them, and charge fees. We’re in a world where submitting 10 times to the same journal in a single year is not only normal, but encouraged. Where poets are now getting PhDs but also not going into academia because tenure-track jobs have disappeared. People still want to be poets and make their mark, but the definition of how a mark is made has shifted. There is still nothing and everything at stake. At the same time, and more importantly, I love how there are not just white dudes and tokens anymore—the field feels more diverse, and it has improved the poems I read.

CS: Yes, I love how it’s more diverse now too and am very excited by many poets who began publishing in the 21stcentury. You mentioned you might do a reading where you emphasize reading these “poetryland poems.” Have you? I feel this could be useful to younger writers who are trying to form more supportive communities, as well as those who are sick of worrying where they belong or fit. Even if you don’t share your own writing with your students, I imagine that when a student expresses a desire to be published or do readings, your experience in this school of hard knocks provides excellent, caring, advice. Is there anything you want to say about these?

DN: Now that you have asked, and reminded me about that, I should definitely schedule a Poetryland Only Reading. So when this thing is published, I will have a link!

Most of the students I teach aren’t writers, and that, to me, is refreshing. It feels gratifying to know I am the first teacher to show them what some aspects of creative writing is, how it can improve their lives, no matter what they go on to do after college. I have some experience helping students get published or doing readings or making their way in the literary world. Not as much as I gather from other professor-types who teach at, say, MFA programs. When students do ask or express interest, I totally help and encourage them and offer them a realistic outlook on how things will be. I have always edited literary journals, and for the past 10 years or so, the one I edit, Pine Hills Review, is loosely affiliated with my college, and students help edit it as interns or as part of a class. That sort of hands-on experience feels interdisciplinary and organic to the student profile I have at my current job.

For many of my students, I know I am not the ideal mentor—I’m just a working class white guy from South Jersey. So a lot of my help comes from helping my students find their communities, whether it’s Cave Canem or Kundiman or VIDA or other places. Most of my students don’t even know there are these institutions out there, waiting for them to feel like they can be part of supportive communities. I do feel like that is real mentorship and good advice. I have former students who have gone on and done MFA programs or have gotten published, and have made their way into the world in ways I never did. That’s mind-blowing at this point.

CS: It makes me happy to hear you so gratified by being the introductory teacher (me too). You mention the digital technologies that emerged in the 90s may necessitate a “fractured and even granular poetics,” and how Trinidad’s Notes on a Past Life helped you write narrative poems again without the fear of being uncool or “mainstream” or “bourgeois.” One of the reasons I’m drawn to the narratives of Harsh Realm is that, in an age where the fragmentation of the digital realm is so culturally omnipresent, the attention and the discipline required to actually construct a more meditative sustained narrative becomes more and more attractive. Yet, beyond any argument of “what the age demanded” (perhaps a kind of deacceleration of its grimace), I feel your narratives do make room for what you call “the granular.” Would you like to elaborate on any of these formal concerns of your poetics, or your revision process?

DN: I would like to think that the process a poem that I write takes—from reading poems of other people, thinking about language in my head, listening to music, scratching notebooks and poem drafts—has gotten more genuine or true to what kinds of poems I can best write. I am not sure I was consciously thinking I was kicking it old school or whatever in the poetic modes department, but I do think that, after returning to writing poems on a more consistent basis after a bunch of prose projects, I didn’t feel the weight of technique anymore, at least not as much as in the past.

CS: Is reading poems by others the usual way you begin the process of writing a poem? Are there any poems in Harsh Realm that came about without reading poems by other people?

Reading other writers definitely would be one of several ways a poem might begin. I mentioned Diane Seuss and David Trinidad. Lucille Clifton and Fernando Pessoa are always on my desk. I’m a huge fan of Matthew Lippman, who wrote about this book, and he indirectly led me back to reading Gerald Stern. I wrote an essay about being a student of Philip Levine for a collection a few years back, and that led to a poem in the collection that imitates his 1992 poem, “On the Meeting of Garcia Lorca and Hart Crane.” It’s called “On the Meeting of Frank O’Hara and David Lee Roth.” At the same time, there are things I read and listen to and enjoy immensely that just don’t find their way into my poems. I’m cool with it, but I don’t think anyone who reads my poems would guess I am a huge sound poetry freak. Slam poems, too, although that might peek through. But sound poets and Language and post-Language poets, love them all, but they don’t show up in my poems. It’s like when CC Deville of Poison jokes about about all his influences—Hendrix, Jimmy Page—and he ends up playing Poison songs. That’s me.

I don’t think I am alone when I talk about the interferences and distortions that come along. There’s the anxieties of influences and the social, coterie aspects in poetry scenes—again, I would like to think—has been put in a less pronounced place. I’m being super-general here, I know. But what I am trying to say is that I worry less about what I think people think, what other poets think. I trust my instincts for when a poem is going to happen.

For example: I feel like I’ve always had a feel for the line, or a particular line that I can identify with as having some sort of meaning or feel to them. It wasn’t always that way. For example, even though I got a lot of pleasure out of it, I was worried I was somehow retrograde in thinking or hoping each of my lines would have its own world of meaning, independent of the poem. It’s sort of an “every frame a painting,” fetishy habit I picked up in workshops over the years, and it directly influenced how I break the line. Breaking before syntactical units so that each line seemed like some complete thought, that seemed to me to be a given when breaking lines. But over the years, I have tried to disrupt that practice and let lines hang and even lose track.

These thoughts really come to the fore when I think of some of the more narrative poems in the collection, like “The Death of College Rock: September 5, 1995,” which recounts an episode of wandering around New York and catching an awards show on a TV. The lines get shorter for me, to give some tension to the grammar and syntax, and I also think it reflects the jumpiness of the time, of being in your late twenties and not knowing what the fuck is happening. What also comes to mind is returning to older styles I used when I was younger, like when I had the influence of certain William Carlos Williams poems hard-coded in my drafting process.

CS: Revisiting this poem in light of your comments, I am struck by how my earlier question totally ignored the importance of the final line, in which the cultural opinions yield to the character of the speaker (figure becomes ground?); but thinking about lines, perhaps an excerpt could illustrate:

“If you were to establish

which songs were objectively awful,

this song would be the index case

against which all other objectively

awful songs were compared.”

I like the way this seems like a straightforward discursive statement, but in these medium length lines “objectively awful,” in the second line becomes “objectively/awful” as if to highlight the emotion of disgust the speaker feels in a hyperbolic self-mocking statement. I can hear your voice in this performative rhetorical utterance. I imagine gestures. I wonder if you prefer to read this slower at readings to emphasize the line breaks and the tension that creates?

DN: Right, I am delighted you picked that up. The enjambment right there to me would be an example of me doing work to avoid the directly prosaic when a reader encounters the poem. At least with my own performer’s tool box, I might even speak in the iambic lockstep “poet voice” to play up that enjambment, so listeners would get that I am disrupting the syntax there. It’s also a good example of my breaking my earlier habits of having lines work as independent units of meaning, because when you’re writing a poem that has narrative or expository surface, another way to compress language and give it energy, it seems to me, is to introduce enjambment.

CS: I also like the way the social milieu you describe/invoke in “poetryland” differs from that of “players in horrible rock bands, or those who care to remember true failure---wordless, naked-ass failure.” (“Hot Blooded,” 33). The meanness, and the sharp wit of the contentious ego-based poetry scene seems muted in the more collaborative art of music making. Arguments happen, but more in form of lighter banter, as in the 3rd paragraph/stanza of “Hot Blooded.”

“After the gig, the singer’s girlfriend complains in her thick Danish accent that she cannot hear ze words. It makes sense that she wants to hear her man sing about her ass. Taking a page from literary theory, I explain that sometimes words aren’t important, that the simple sound of her husband’s easel-aided utterances would suffice. She rolls her eyes and carries her old man’s antediluvian teleprompter out to the cab.”

And while there may be arguments about arrangements and aesthetics, but in “The Drummer in Our Band Tells Us He’s a Virgin,” they fade into moments of brotherly vulnerability and even, if compared to the poetryland poems, a kind of tenderness. Woven through this relatively straightforward narrative we see references to Othello. I admire the way you handle this “digression device.” For me, it could suggest what the speaker is thinking while this situation is happening, and this breathes mystery into the poem that can come in form of questions: How does this band practice scene connect to a Kabuki production of Othello, with an overblown “honest Iago?” I’m not asking you to talk about your “intention” on a meaning-level here, but if you’d like to add, or correct me on, anything here, I’d love to hear…

DN: I’ve been saying to people I feel more comfortable in music-related spaces—stores, clubs, gigs, practice spaces—than I ever was in literary spaces. Maybe it’s because in a music store it’s a once-removed situation, or there was no pressure to not suck, because I knew I sucked, or didn’t care that I sucked.

That poem about one of playing in my bands goes back a ways, but I do remember thinking the memory of watching a kabuki Othello production was related to this moment in the rehearsal space in the East Village. I wish I could make these digression device-type leaps more consciously or artfully, which is how I am taking your characterization, perhaps hopefully. I was having fun and pleasure with the assonance of that long o-sound. Bubbling underneath is the beta machismo of how some bands passive-aggressively argue with each other, in a small room but with microphones, and what I remember about Othello the most is how Iago orchestrates a whole sequence of events.

CS: Do you still make music?

DN: I do still play guitar, albeit really badly. I love the gear, the amps and pedals. I yearn to be in a band again, to play with other people. It’s probably unlikely to happen, although my daughter plays drums now, and someday I may go downstairs and plug in. Just to jam and get loud.

CS: A family band would be great! On a more micro level, as I reread this book, I look back over the many lines, or short passages, I’ve underlined, and quite a few of them are about language and metaphysics, in a rather casual offhand, and funny, way:

“Someone way write, ‘What is feeling?’ Someone answers: ‘It’s kind of like consciousness, dear, except you give it some goddamn value.’” (8—The Art of Prose (with Digressions)

Sometimes the word “God”, makes an appearance, in unexpected ways. One poem ends with “Let God’s love ruin it. And God’s love always ruins it” (31). And another writes: “Hint: it appears very likely our faith in God interrupts whatever truly tries to speak to us, which is a version of us, of course.” (56). Both of these lines are from poems addressed to a “You” uttered with an authority and a tone of wisdom, but do not belabor their points. I don’t feel atheism as much as a sense of letting go from reified words that get in the way of feeling, or should I say consciousness?

DN: You’re talking about a strand of poems of mine I feel less sure-footed talking about, poems where I am letting go of meaning as much as I can. I am forever hoping a poem will come through me in ways that are less conscious. I think that it’s in poetry where half-knowledge, or half-understanding things, can somehow become something else. And I suppose there’s where metaphysics and attempts at a variety of aphoristic experience comes into the mix. In my best moments looking at poems, I notice shades of meaning pop up that I did not intend but still add to the poem. That, to me, is the attraction to writing a certain kind poem; it’s a field of answers looking for questions. When that distills even further, I find mentions of God and faith popping up. That’s not just twelve years of Catholic school rearing its head, although it’s a part of it. It’s post-faith me trying to come up with a referent to all of those things I can’t figure out or don’t want to figure out. God’s the best name for it, at least in some poems.

CS: I recently quoted your attraction to a poem as “a field of answers looking for questions,” to a friend, and love what you say about the process of letting go of meaning. The book’s final poem, for instance, I read at first as making an important point about “sad cowboy songs,” but the more I reread it, the weirder it gets, and meaning “becomes something else.” Regardless of what some idea of “the reader” thinks, do you find sometimes that, when reading your own poems in this collection that they step outside of their utterance and can inspire you to feel different questions than you were aware of when writing them, like the old adage of poems knowing more than the poet does?

DN: I don’t know if other poets feel this, but it takes a lot of work to let go and trust the language. Sometimes when I do that, the language ends up as a load of goo. I have notebooks upon notebooks of that kind of stuff: failed experiments and starts.

And then a poem comes along like “On Realizing Poison’s ‘Every Rose Has Its Thorn’ Has the Same Chords as the Replacements’ ‘Here Comes a Regular,’” the poem you’re referring to, and it feels like the language and negative capability falls into place. That long title does the expository heavy lifting, and lets readers know exactly what the poem that follows addresses, but it’s not just addressing something I suspect you know, as a real musician: there’s only so many chord progressions, only so many ways to put together a song, so of course there are going to be overlaps and, to me at least, versions of pastoral, a green world where different aesthetic impulses co-exist. It’s a possibility that I am always looking for, intersections of style and intentionality, the fields that I am talking about would be both in the mind and on the page, where we can at once acknowledge differences and clashes as well as find poetry.

CS: Scattered throughout Harsh Realm are a few poems that bring your 21st century more domestic life into the picture, for instance “Future Days”(42-3). After navigating a page and half of memories, both dark and light, from the 90s framed in a more recent present, the poem swerves into a more stammering cadence as the memories get closer:

Alone with my headphones and coffee straws,

passwords written in chalk on bricks gather light from a window,

and I remember the day in the hospital just down the street

from here in Albany, in the second-string coffee shop

with high windows, when my daughter’s legs turned blue

last summer, and I couldn’t drive straight or walk straight,

and I ran into the room where she was in bed and she was

OK but scared to have her face with tubes in it. My chest

froze there in the hallway, and I touched her small ears

and sang her name a little bit—it was all I could do to stand there

too appear fatherly, to breathe in and out, helpless and still.” (43---Future Days)

“Eavesfall” (40) and “Gethsemane” (62) are ‘lighter,’ poems also set in a domestic present. I find “Gethsemane” especially refreshing and charming, after these darker poems from the 1990s. The exchange between father and daughter, for me, has a kind of Frank O’Hara insouciance of “deep gossip,” in ways the poetry coteries (of the 90s at least) could’ve used more of. I wonder if you’ve written more poems like this; it makes me happy to see this speaker in the present. Have you shown any of these to your daughter?

DN: It’s funny you put “Future Days” and “Gethsemane” in the same question, along with “Eavesfalls,” but I guess it makes sense. Each mentions my daughters, or a daughter, and maybe their presence grounds some of the more highfalutin pantheistic feelings in the poems we just talked about. “Future Days” was a bear of a poem to stick with—I felt it had that “I do this, I do that” thing going for it, and the form of it felt open enough to throw in everything from the annoying dude who talked out loud every day in my local coffee shop and memories of poetry readings in Brooklyn where no one showed up.

CS: It’s nice to see people respond to that poem on Facebook.

DN: To go back to another question, “Future Days” is a poem where I was trying out new ways of thinking about the line, and where words could break and still mean something but also disrupt an easy, comfortable reading experience. I also think “Future Days” is important for the collection, since it brings together memories of Poetryland’s absurd focus on who is doing what and why things don’t happen, with what happens every day: people drink crappy coffee, students in graduate school struggle with their papers, the kids we have end up in emergency rooms. And the more I thought about this, the more I thought about how Can and Neu! and the motorik drum beat relates to how I was living my life, or trying to: it’s a rhythm that’s a “restrained exhilaration,” is how it’s described somewhere. It’s how I try to actively listen to music while trying to write at the same time.

In the course of answering these questions you’ve asked, I do notice I am often setting up one tendency against another—narrative versus lyric maybe, darker poetryland poems versus lighter ones from the present. I don’t necessarily think it’s healthy to do this, but more and more I feel it’s part of my process: I’ll write one way in reaction or rebellion to another way, or write about one subject as a way of getting away from a topic I can’t stand exploring anymore. When people read these poems, they may not realize these are moments that happened years ago, and that’s intentional: I do want readers to think I am writing something that just happened yesterday and they’re getting the immediate reaction. For me at least, it’s those poems that are the most challenging to pull off, and not just because of writing in the present tense or anything like that. It’s the challenge of keeping that immediacy and deep gossip in the poems as they move through drafts. I have to work really hard to make those poems seem easy, whereas other poems that draw from more definite timelines in the past may come more naturally. My oldest did read “Gethsemane” when it was published, and what was great is I had to explain where the title came from, all the temptations of Christ and the stations of the cross. She had no clue about any of it. So just to get her up to speed on the title, I had to give her a crash course on Jesus. Her reaction to that was as if I was telling her the story of some musical artist from the 80s that just went viral on TikTok—it had relevance but not really. It was refreshing, at least to me, that she wasn’t burdened with religion. I’ve been writing poems about some of this. Maybe that’s the next book.